Video Poem in Drunken Boat

A video poem of mine appears in the new issue of Drunken Boat. Formally, this poem is what I’d call a Tennessee crown. Unlike a proper, contemporary crown of sonnets, such as Patricia Smith’s stunning “Motown Crown”, my Tennessee crown turns with the spirit of the jester, moving through the gallows humor of healthcare workers.

Thank you, editors of Drunken Boat, for including me in this issue of one of my favorite online journals.

For more of my video work that originally appeared in Drunken Boat, see “Lettie from the Ocean,” an interactive piece designed for the iPhone.

Reading with Drunken Boat

The online journal, Drunken Boat, will celebrate the launch of its newest issue with a virtual party on Tuesday, March 12 at 8:00 PM eastern time. At the launch event, contributors including me will read work from this exciting issue.

I am so honored to be included in the latest Drunken Boat, now edited by students at Tufts University under the guidance of Founding Editor, Ravi Shankar, and the Director of The NEXT, Professor Dene Grigar.

To join the launch party, follow the Zoom link: https://tufts.zoom.us/j/3481482573

Reading for Washington Square Review

This week I had the opportunity to read with my fellow contributors to the wonderful recent issue of Washington Square Review. Organized by editor Melissa Ford Lucken and Dave Wasinger, the reading was a true pleasure to experience as a reader and listener.

You can find the recording of the event here. My own contribution is around the 1:28:14 mark.

Many thanks to Melissa and Dave and all the editors at Washington Square Review.

Poems in Washington Square Review

Please join me on Monday, October 23 at 7:00 PM EST, for a reading of work from the most recent issue of Washington Square Review. I have three poems in this issue, available for purchase here, edited by Melissa Ford Lucken. I will be reading with many of my wonderful co-contributors.

You can register here for the Zoom link.

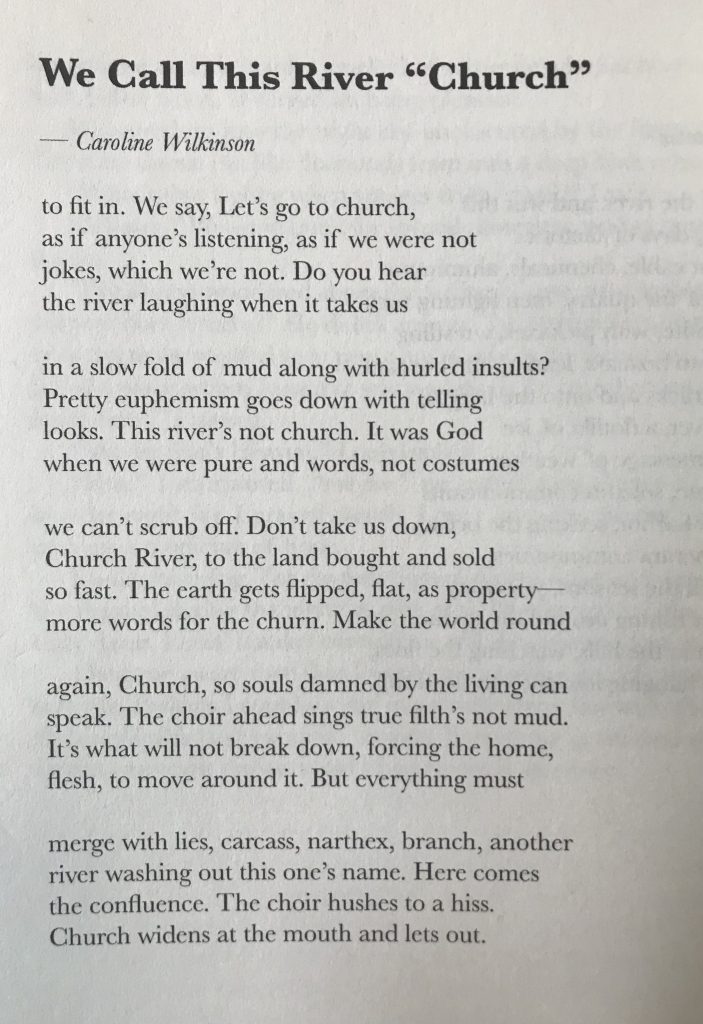

Below is one of my poems published in the issue, “We Call This River ‘Church'”:

New Article in NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction

My article on the influence of the Underground Railroad on the plot of Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady appears in the most recent issue of NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction. The article focuses on a house in James’s masterpiece that the author based on his grandmother’s home in Albany, New York. This grandmother, Catharine James, whom the novelist stayed with as a boy, lived near numerous stations on the Underground Railroad.

While The Portrait of a Lady features an unusual number of grand homes, the Albany house is not one of them. One critic, Marilyn Chandler, characterizes the home as an “architectural joke” compared to the other houses in the novel. When Isabel first meets the aunt who takes her out of Albany to Europe, this aunt, Mrs. Touchett, calls the home “very bad” and “bourgeois.” (Mrs. Touchett lives in a more typical house in the world of The Portrait of a Lady, an Italian castle.)

I argue that the “very bad” house in Albany operates as a spatial representation of the novel’s plot — or to use the term preferred by James, the novel’s “ado.” In the preface to The Portrait of a Lady, James calls the word plot “nefarious” before reflecting on the process of creating an “ado” for Isabel in terms that evoke the “square” and “large” Albany house. He metaphorically describes constructing the novel’s narrative action as building a “square and spacious house” around his isolated heroine. Isabel when staying in Albany remains notably isolated, choosing to be alone. She consistently appears in a room whose door to the “vulgar street” is bolted shut and “condemned.”

In my analysis of the Albany house as a symbol of the novel’s plot, I consider the history of the upstate city in different decades, including the 1850s when Isabel daydreams in front of the bolted door and the Underground Railroad was particularly active in Albany. I ultimately assert that the history of Black people in the US crossing regional and national borders in the 1850s in pursuit of freedom centrally and problematically determine James’s highly influential plot about an innocent, white American woman travelling to Europe in search of personal freedom.

To read the article, please visit NOVEL‘s site. If you cannot get past the paywall, you can download a pdf of the article at Academia.edu.

Story in Menagerie Magazine

In the new issue of Menagerie Magazine is a short piece of mine, “Panicle.”

Thank you, Steve Woodward, co-founder and editor of Menagerie for including this story about the strange joys of exclusion.

Dubravka Ugrešić

I am sad to learn the news of Dubravka Ugrešić’s death. Her fiction is always surprising and often moving. I wrote about her brilliant novel, The Ministry of Pain, which explores the power of memory along with the mercy of forgetting.

Ugrešić lived in exile both in the US and Europe after her home country, Yugoslavia, fell apart and became Croatia. Uncompromising and insightful, she criticized not only Croatia’s nationalism but also the US’s consumerism and superficiality. She consistently examined the seemingly well-meaning individual to reveal how political and social circumstances affect the spirit and mind.

For a 2018 article in The New Yorker, Christopher Byrd spoke with Ugrešić, who was in the US to promote her collection of essays, American Fictionary. Ugrešić’ compared the then-President of the United States, Donald Trump, to the leadership in her broken home country in the wake of war. Invoking an immense world at the mercy of bad leaders, Ugrešić’ said of Trump: “He’s showing vividly that something is wrong with all of us, if we are able to have such leaders.” She went on to say of her “poor Yugoslavia”: “It had the most stupid leaders you can imagine.” Such leaders, she told Byrd, “just eat these countries like chocolate.”

Update April 10: Lit Hub has published wonderful remembrances of Ugrešić’ by five translators of her work, Celia Hawkesworth, Mark Thompson, David Williams, Vlad Beronja, and Ellen Elias-Bursać, who offers an introduction to this “expatriate citizen of the Republic of World Letters.”

Juliet Patterson’s Threnody

Juliet Patterson’s book of poems, Threnody, imparts an intimate sense of annihilation. Its thematic exploration of dying bees ultimately reveals a violence that pushes up against oceans, rivers, and skin. In “Dark Scaffolding,” a “We” draws us inside the poem’s enjambed lines where both words and heat press against the flesh:

The drift

and slip of body along shoreline’s seam

unlocked to day’s heat retracks the ringing

tide. We press our face to its changing ink; cluster

and drone, a blindsight to listening.

In a book in which images from distant wars appear on shorelines, this “drone” written in “changing ink” suggests not only a bee but also a military aircraft or ship. With a “blindsight to listening,” Patterson moves beyond the well-known idea that we cannot grasp destruction as large as global warming or endless war. In Threnody, Patterson offers a more neglected truth: that we sense this violence even when we cannot consciously perceive it.

With its balance between the intimate and the vast, Patterson’s threnody — a poetic form in which the dead are lamented — renders ecological destruction with unexpected, emotional power. The changing oceans suffer a sickness understood by the human body, being “raw, sick and hot.” A grove of pines endures the unfavorable conditions of the era with a sickly promise that pains in its detail:

as if each turgid node

might blossom

and bring, would bring

us as offering,

barter, the armament

and image

of the spray

and spore.

Through clear images that simultaneously evoke the individual existence and our shared earth, Threnody brings global destruction close without reducing the scale of the loss.

I have admired Patterson’s poems for many years, having first read her work in literary journals prior to the publication of her brilliant, debut book, The Truant Lover. In DIAGRAM, I reviewed her chapbook, Dirge, published in the same volume with Elementary Rituals by Rachel Moritz whose haunting book, Night-Sea, I also wrote about on this website. Threnody is available from Nightboat Books, which also published Patterson’s The Truant Lover as the winner of the press’s book contest judged by Jean Valentine.

Experimental Victorians

I have always viewed Victorian novels — at least my favorite ones — as profoundly strange, so I found such satisfaction in reading Elaine Freedgood’s Worlds Enough: The Invention of Realism in the Victorian Novel. Freedgood looks at how critics came to interpret the genre of the Victorian novel as more straightforwardly realistic and formally cohesive than it is.

Her argument is clear, her jokes, funny. I found the book particularly fun to read as someone who adores how Victorian novelists can make the world turn strangely, as Dickens does in Our Mutual Friend in a dinner-party scene that Freedgood addresses. She specifically examines J. Hillis Miller‘s critical interpretation of this scene in which the narrator looks down at events from the perspective of a mirror in the dining room. This mirror reflects the party’s two hosts, Mr. and Mrs. Veneering, and their guests:

The great looking-glass above the sideboard, reflects the table and the company. Reflects the new Veneering crest, in gold and eke in silver, frosted and also thawed, a camel of all work….Reflects Veneering; forty, wavy-haired, dark, tending to corpulence, sly, mysterious, filmy—a kind of sufficiently well-looking veiled-prophet, not prophesying. Reflects Mrs Veneering; fair, aquiline-nosed and fingered, not so much light hair as she might have, gorgeous in raiment and jewels, enthusiastic, propitiatory, conscious that a corner of her husband’s veil is over herself. Reflects Podsnap; prosperously feeding, two little light-coloured wiry wings, one on either side of his else bald head, looking as like his hairbrushes as his hair, dissolving view of red beads on his forehead, large allowance of crumpled shirt-collar up behind. Reflects Mrs Podsnap; fine woman for Professor Owen, quantity of bone, neck and nostrils like a rocking-horse, hard features, majestic head-dress in which Podsnap has hung golden offerings.